Top-down approach

Because creating a language is not a short task, during project development I will strongly rely on a top-down approach.

Instead of going through the details of each module separately I will describe all of them at once in the most minimalistic way.

After each iteration I will add some new feature to the project describing it in more detail.

Sources

The project can be cloned from github repository.

The revision described in this post is 50e6996a4faf8d5b469d291a029be05f9e6c9520.

Features

In this post I will add following features to the Enkel language:

- Declare variables of type int or string

- Print variables

- Simple type inference

So let’s start by creating the most minimalistic implementation to make first lines of Enkel language run on a JVM.

This is the code that will be executed at the end of the day:

//first.enk

var five=5

print five

var dupa="dupa"

print dupa

Lexing and parsing with ANTLR4

I started by implementing lexer from scrach but it seemed like a very repetetive task.

After browsing web for a while I came across awesome tool called “Antlr”. You just just “feed” it with a schema-like file describing rules of your language

and it provides you a way to traverse an Abstract Syntax tree (also called ‘parse tree’).

Let’s start by creating very simple rules for the language:

//header

grammar Enkel;

//parser rules

compilationUnit : ( variable | print )* EOF; //root rule - globally code consist only of variables and prints (see definition below)

variable : VARIABLE ID EQUALS value; //requires VAR token followed by ID token followed by EQUALS TOKEN ...

print : PRINT ID ; //print statement must consist of 'print' keyword and ID

value : NUMBER

| STRING ; //must be NUMBER or STRING value (defined below)

//lexer rules (tokens)

VARIABLE : 'var' ; //VARIABLE TOKEN must match exactly 'var'

PRINT : 'print' ;

EQUALS : '=' ; //must be '='

NUMBER : [0-9]+ ; //must consist only of digits

STRING : '"'.*'"' ; //must be anything in qutoes

ID : [a-zA-Z0-9]+ ; //must be any alphanumeric value

WS: [ \t\n\r]+ -> skip ; //special TOKEN for skipping whitespaces

The code is mostly self-explanatory but there are few things worth noticing:

- EOF - end of file

- space beetween rule content and ‘;’ is mandatory

Once the rules are defined you have to run antlr tool to generate Java classes:

This tool generates 4 classes:

- EnkelLexer - contains tokens information

- EnkelParser - contains parser, tokens information and inner class for each parser rule.

- EnkelListener - provides callbacks for parse-tree events when it visits nodes

- EnkelBaseListener - Just an empty implementation of EnkelListener

For library user the most important is EnkelBaseListener. it provides nice callbacks while the alghoritm is walking the tree - we do not need to worry about Lexer and Parser classes - antlr library nicely separates it from us.

After compiling all java classes using javac *.java it’s time to test the rules. There is one useful tool inside antlr library, written exactly for that purpose - org.antlr.v4.gui.TestRig:

$ export CLASSPATH=".:$ANTLR_JAR_LOCATION:$CLASSPATH"

$ java org.antlr.v4.gui.TestRig Enkel compilationUnit -gui

var x=5

print x

var dupa="dupa"

print dupa

ctrl+D //end of file

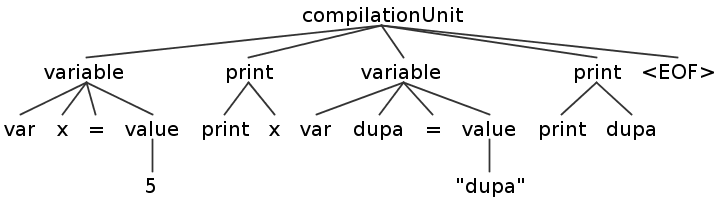

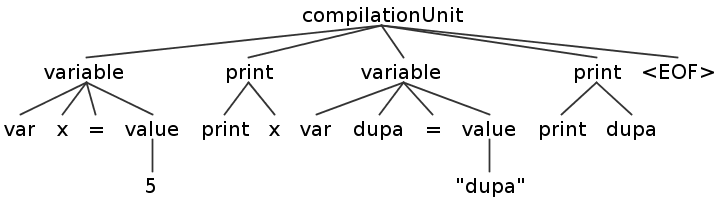

Above command generates visual representation of parse tree:

I find myself using -tokens option on regular basis too. It prints matched tokens info (type,line number etc.).

Walking the parse tree

Antlr provides a way to walk (visit) parse tree elements by subclassing generated EnkelListener:

EnkelTreeWalkListener.java

public class EnkelTreeWalkListener extends EnkelBaseListener {

Queue<Instruction> instructionsQueue = new ArrayDeque<>();

Map<String, Variable> variables = new HashMap<>();

public Queue<Instruction> getInstructionsQueue() {

return instructionsQueue;

}

@Override

public void exitVariable(@NotNull EnkelParser.VariableContext ctx) {

final TerminalNode varName = ctx.ID();

final EnkelParser.ValueContext varValue = ctx.value();

final int varType = varValue.getStart().getType();

final int varIndex = variables.size();

final String varTextValue = varValue.getText();

Variable var = new Variable(varIndex, varType, varTextValue);

variables.put(varName.getText(), var);

instructionsQueue.add(new VariableDeclaration(var));

logVariableDeclarationStatementFound(varName, varValue);

}

@Override

public void exitPrint(@NotNull EnkelParser.PrintContext ctx) {

final TerminalNode varName = ctx.ID();

final boolean printedVarNotDeclared = !variables.containsKey(varName.getText());

if (printedVarNotDeclared) {

final String erroFormat = "ERROR: WTF? You are trying to print var '%s' which has not been declared!!!111. ";

System.out.printf(erroFormat, varName.getText());

return;

}

final Variable variable = variables.get(varName.getText());

instructionsQueue.add(new PrintVariable(variable));

logPrintStatementFound(varName, variable);

}

private void logVariableDeclarationStatementFound(TerminalNode varName, EnkelParser.ValueContext varValue) {

final int line = varName.getSymbol().getLine();

final String format = "OK: You declared variable named '%s' with value of '%s' at line '%s'.\n";

System.out.printf(format, varName, varValue.getText(), line);

}

private void logPrintStatementFound(TerminalNode varName, Variable variable) {

final int line = varName.getSymbol().getLine();

final String format = "OK: You instructed to print variable '%s' which has value of '%s' at line '%s'.'\n";

System.out.printf(format,variable.getId(),variable.getValue(),line);

}

}

getInstructionsQueue returns all instructions in correct order that later will be converted to JVM bytecode.

Once the listener is implemented it is time to register it:

SyntaxTreeTraverser.java

public class SyntaxTreeTraverser {

public Queue<Instruction> getInstructions(String fileAbsolutePath) throws IOException {

CharStream charStream = new ANTLRFileStream(fileAbsolutePath); //fileAbolutePath - file containing first enk code file

EnkelLexer lexer = new EnkelLexer(charStream); //create lexer (pass enk file to it)

CommonTokenStream tokenStream = new CommonTokenStream(lexer);

EnkelParser parser = new EnkelParser(tokenStream);

EnkelTreeWalkListener listener = new EnkelTreeWalkListener(); //EnkelTreeWalkListener extends EnkelBaseLitener - handles parse tree visiting events

BaseErrorListener errorListener = new EnkelTreeWalkErrorListener(); //EnkelTreeWalkErrorListener - handles parse tree visiting error events

parser.addErrorListener(errorListener);

parser.addParseListener(listener);

parser.compilationUnit(); //compilation unit is root parser rule - start from it!

return listener.getInstructionsQueue();

}

}

I have also written simple listener for Error handling:

//EnkelTreeWalkErrorListener.java

public class EnkelTreeWalkErrorListener extends BaseErrorListener {

@Override

public void syntaxError(Recognizer<?, ?> recognizer, Object offendingSymbol, int line, int charPositionInLine, String msg, RecognitionException e) {

final String errorFormat = "You fucked up at line %d,char %d :(. Details:\n%s";

final String errorMsg = String.format(errorFormat, line, charPositionInLine, msg);

System.out.println(errorMsg);

}

}

Parse tree listeners are implemented.It is time to run the SyntaxTreeTraverser.

To do that I created Compiler class which is the startpoint of the compiler.

It takes an argument (full path to the file to be parsed).

//Compiler.java

public class Compiler {

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

new Compiler().compile(args);

}

public void compile(String[] args) throws Exception {

//arguments validation skipped (check out full code on github)

final File enkelFile = new File(args[0]);

String fileName = enkelFile.getName();

String fileAbsolutePath = enkelFile.getAbsolutePath();

String className = StringUtils.remove(fileName, ".enk");

final Queue<Instruction> instructionsQueue = new SyntaxTreeTraverser().getInstructions(fileAbsolutePath);

//TODO: generate bytecode based on instructions

}

}

Now I have fully standalone application that can validate my *.enk files!

It won’t compile it or run yet, but at least it will validate with following rules:

- Allow to declare variable using syntax like ‘var x=1’ or ‘var x=”anything”’

- Allow to print variable using syntax like ‘print x’

- Print errors if the code has syntax not matching above rules

Let’s test the following sample first.enk:

var five=5

print five

var dupa="dupa"

print dupa

$java Compiler first.enk

OK: You declared variable named 'five' with value of '5' at line '1'.

OK: You instructed to print variable '0' which has value of '5' at line '2'.'

OK: You declared variable named 'dupa' with value of '"dupa"' at line '3'.

OK: You instructed to print variable '1' which has value of '"dupa"' at line '4'.'

ErrorListener should also be able to detect unexpected patterns.

After adding a line void noFunctionsYet() the “compiler” prints:

You fucked up at line 1,char 0 :(. Details:

mismatched input 'void' expecting {<EOF>, 'var', 'print'}

Generating bytecode based on instructions queue

Java .class files consist of set of instructions

(https://docs.oracle.com/javase/specs/jvms/se7/html/jvms-6.html).

Each instruction consist of:

- Opcode (one byte) - specifies operation to be done

- Optional Operands - input to instruction

Example: iload 5 (0x15 5) - loads int value from local variable, where 5 is an index in local variables array.

Instructions can also pop values from operand stack and push onto it. Example:

It would load int variable from local variables index 3, and another variable at index 2. At that point

the stack would contain two int variables. After iadd is called two integer values are “consumed” by

iadd operation and the result is pushed onto stack.

ASM

There is an useful java tool for manipulating bytecode called ASM. It separates you from the instructions byte values.

You do not have to care about actual values of the instructions (was iload 0x15 or 0x16?) and writing them to file.

You just have to remember names of the instructions - it maps them to values and saves to file automaically.

Instruction interface

SyntaxTreeTraverser while visiting tree nodes stores them into instructionsQueue.

This queue can have values of type Instruction:

public interface Instruction {

void apply(MethodVisitor methodVisitor);

}

It requires every implementations too do some bytecode instructions using methodVisitor (ASM library) object.

//Compiler.java

public void compile(String[] args) throws Exception {

//some lines deleted -> described in previous sections of this post

final Queue<Instruction> instructionsQueue = new SyntaxTreeTraverser().getInstructions(fileAbsolutePath);

final byte[] byteCode = new BytecodeGenerator().generateBytecode(instructionsQueue, className);

saveBytecodeToClassFile(fileName, byteCode);

}

//ByteCodeGenerator.java

public class BytecodeGenerator implements Opcodes {

public byte[] generateBytecode(Queue<Instruction> instructionQueue, String name) throws Exception {

ClassWriter cw = new ClassWriter(0);

MethodVisitor mv;

//version , acess, name, signature, base class, interfaes

cw.visit(52, ACC_PUBLIC + ACC_SUPER, name, null, "java/lang/Object", null);

{

//declare static void main

mv = cw.visitMethod(ACC_PUBLIC + ACC_STATIC, "main", "([Ljava/lang/String;)V", null, null);

final long localVariablesCount = instructionQueue.stream()

.filter(instruction -> instruction instanceof VariableDeclaration)

.count();

final int maxStack = 100; //TODO - do that properly

//apply instructions generated from traversing parse tree!

for (Instruction instruction : instructionQueue) {

instruction.apply(mv);

}

mv.visitInsn(RETURN); //add return instruction

mv.visitMaxs(maxStack, (int) localVariablesCount); //set max stack and max local variables

mv.visitEnd();

}

cw.visitEnd();

return cw.toByteArray();

}

}

Because Enkel does not (yet) support methods, classes, or scopes

the compiled class is a subclass of Object which has only main method.

After specifing that I need to provide size for local variables and maximum size for a stack.

Afterwards each instruction adds something to the bytecode in a loop. There are currently

2 type of instructions:

//VariableDeclaration.java

public class VariableDeclaration implements Instruction,Opcodes {

Variable variable;

public VariableDeclaration(Variable variable) {

this.variable = variable;

}

@Override

public void apply(MethodVisitor mv) {

final int type = variable.getType();

if(type == EnkelLexer.NUMBER) {

int val = Integer.valueOf(variable.getValue());

mv.visitIntInsn(BIPUSH,val);

mv.visitVarInsn(ISTORE,variable.getId());

} else if(type == EnkelLexer.STRING) {

mv.visitLdcInsn(variable.getValue());

mv.visitVarInsn(ASTORE,variable.getId());

}

}

}

It is worth noticing that there is already some small fraction of

type inference implemented. The types are deduced dynamically based

on the token that was lexed during file parsing! Thanks to it I was able

to execute different instructions based on the type:

visitInsn - visit instruction - 1 parametr is a opcode (instruction), and second is an operand.BIPUSH - pushes an byte (integer) value to the stackISTORE - stores int in local variable. It takes an index of local variable as an operand. It pops int value from a stackASTORE - same as ISTORE but “A” means reference (very intuitively). It needs to be saved as a reference beacause String instances are an objects.

Second Instruction type:

//PrintVariable.java

public class PrintVariable implements Instruction, Opcodes {

public PrintVariable(Variable variable) {

this.variable = variable;

}

@Override

public void apply(MethodVisitor mv) {

final int type = variable.getType();

final int id = variable.getId();

mv.visitFieldInsn(GETSTATIC, "java/lang/System", "out", "Ljava/io/PrintStream;");

if (type == EnkelLexer.NUMBER) {

mv.visitVarInsn(ILOAD, id);

mv.visitMethodInsn(INVOKEVIRTUAL, "java/io/PrintStream", "println", "(I)V", false);

} else if (type == EnkelLexer.STRING) {

mv.visitVarInsn(ALOAD, id);

mv.visitMethodInsn(INVOKEVIRTUAL, "java/io/PrintStream", "println", "(Ljava/lang/String;)V", false);

}

}

}

GETSTATIC - Get static field from class (java.lang.System.out field which is a type of java.io.PrintStream)ILOAD - push local variable to stack (id is a index of a variable in variabiles stack)visitMethodInsn - visit a method instructionINVOKEVIRTUAL - invokes an instance method (call println methond on a field “out” which takes I-integer and return V-void)ALOAD - similar to ILOAD but A stands for reference (String object refherence)

Generate bytecode

After calling cw.toByteArray(); the ASM creates a new instance of ByteVector

and puts all the instructions in it. The very first 4 bytes in EVERY .class files

are 0xCAFEBABE.

Following values are described below:

//https://docs.oracle.com/javase/specs/jvms/se8/html/jvms-4.html#jvms-4.1

ClassFile {

u4 magic; //CAFEBABE

u2 minor_version;

u2 major_version;

u2 constant_pool_count;

cp_info constant_pool[constant_pool_count-1]; //string constants etc...

u2 access_flags;

u2 this_class;

u2 super_class;

u2 interfaces_count;

u2 interfaces[interfaces_count];

u2 fields_count;

field_info fields[fields_count];

u2 methods_count;

method_info methods[methods_count];

u2 attributes_count;

attribute_info attributes[attributes_count];

}

In this post I mainly described method_info section since the Enkle does

not have fields, attributes, superclasses or inerfaces.

Write bytecode to file

There is requirement specified in jvm specification - the .class file has

to be named exactly the same as the class itself. The file passed to compiler

is a “class” name so the output file has to be the same but with different

extension (*enk -> *.class):

//Compiler.java

private static void saveBytecodeToClassFile(String fileName, byte[] byteCode) throws IOException {

final String classFile = StringUtils.replace(fileName, ".enk", ".class");

OutputStream os = new FileOutputStream(classFile);

os.write(byteCode);

os.close();

}

Veryfing .class file

To test results it is good idea to use some tools that can analyze bytecode. There are

many plugins for every modern java ide nowadays just for that. Alternatively you can use javap tool (bundled within jdk):

$ $JAVA_HOME/bin/javap -v file

Classfile /home/kuba/repos/Enkel-JVM-language/file.class

Last modified 2016-03-16; size 335 bytes

MD5 checksum bcbdaa7e7389167342e0c04b52951bc9

public class file

minor version: 0

major version: 52

flags: ACC_PUBLIC, ACC_SUPER

Constant pool:

#1 = Utf8 file

#2 = Class #1 // file

#3 = Utf8 java/lang/Object

#4 = Class #3 // java/lang/Object

#5 = Utf8 Test.java

#6 = Utf8 main

#7 = Utf8 ([Ljava/lang/String;)V

#8 = Utf8 java/lang/System

#9 = Class #8 // java/lang/System

#10 = Utf8 out

#11 = Utf8 Ljava/io/PrintStream;

#12 = NameAndType #10:#11 // out:Ljava/io/PrintStream;

#13 = Fieldref #9.#12 // java/lang/System.out:Ljava/io/PrintStream;

#14 = Utf8 java/io/PrintStream

#15 = Class #14 // java/io/PrintStream

#16 = Utf8 println

#17 = Utf8 (I)V

#18 = NameAndType #16:#17 // println:(I)V

#19 = Methodref #15.#18 // java/io/PrintStream.println:(I)V

#20 = Utf8 \"dupa\"

#21 = String #20 // \"dupa\"

#22 = Utf8 (Ljava/lang/String;)V

#23 = NameAndType #16:#22 // println:(Ljava/lang/String;)V

#24 = Methodref #15.#23 // java/io/PrintStream.println:(Ljava/lang/String;)V

#25 = Utf8 Code

#26 = Utf8 SourceFile

{

public static void main(java.lang.String[]);

descriptor: ([Ljava/lang/String;)V

flags: ACC_PUBLIC, ACC_STATIC

Code:

stack=2, locals=3, args_size=1

0: bipush 5

2: istore_0

3: getstatic #13 // Field java/lang/System.out:Ljava/io/PrintStream;

6: iload_0

7: invokevirtual #19 // Method java/io/PrintStream.println:(I)V

10: ldc #21 // String \"dupa\"

12: astore_1

13: getstatic #13 // Field java/lang/System.out:Ljava/io/PrintStream;

16: aload_1

17: invokevirtual #24 // Method java/io/PrintStream.println:(Ljava/lang/String;)V

20: return

}

Running the very first Enkel code

Finally let’s test the code itself:

var five=5

print five

var dupa="dupa"

print dupa

$java Compiler first.enk

$java first

5

"dupa"